A really practical question for eDNA is: so what? So I can detect all kinds of species in the world with a water/soil/air sample, but what good does that do me, if I already knew these things were there?

The answer, of course, is that there are all kinds of practical reasons that eDNA data might be valuable. An eDNA assay might be more sensitive than other methods of sampling, for example. Or it might be cheaper, more scalable, or more easily automated. But even these advantages might be difficult to sell when existing management programs have been in place for decades — switching methods carries substantial amounts of risk, and there are often institutional barriers to doing so.

So then the next question might be: what information does eDNA give me, relative to what I’m already collecting, and how much marginal benefit does that new information have?

And the answer to that one suggests use-cases that are — to my knowledge, at least — so far relatively rare in the published literature: data-poor situations. The logic goes as follows: if you already have a lot of information about your study system, adding eDNA doesn’t give you much benefit (about the system… although it might be very valuable in terms of assessing the behavior of your eDNA assay). But where you have little existing information, eDNA data is way, way better than what you had before.

Abby Keller’s recent master’s thesis gives the most concrete example that I know of. She’s getting ready to submit it for publication now, but this blog seemed a good place to highlight it.

By Ryan Kelly

A really practical question for eDNA is: so what? So I can detect all kinds of species in the world with a water/soil/air sample, but what good does that do me, if I already knew these things were there?

The answer, of course, is that there are all kinds of practical reasons that eDNA data might be valuable. An eDNA assay might be more sensitive than other methods of sampling, for example. Or it might be cheaper, more scalable, or more easily automated. But even these advantages might be difficult to sell when existing management programs have been in place for decades — switching methods carries substantial amounts of risk, and there are often institutional barriers to doing so.

So then the next question might be: what information does eDNA give me, relative to what I’m already collecting, and how much marginal benefit does that new information have?

And the answer to that one suggests use-cases that are — to my knowledge, at least — so far relatively rare in the published literature: data-poor situations. The logic goes as follows: if you already have a lot of information about your study system, adding eDNA doesn’t give you much benefit (about the system… although it might be very valuable in terms of assessing the behavior of your eDNA assay). But where you have little existing information, eDNA data is way, way better than what you had before.

Abby Keller’s recent master’s thesis gives the most concrete example that I know of. She’s getting ready to submit it for publication now, but this blog seemed a good place to highlight it.

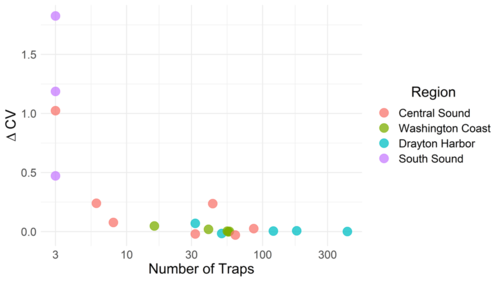

Given this dataset, she could then ask the question I started with: So what? Where did eDNA provide additional value (relative to the existing traps), and where did it not? She found the molecular dataset was particularly valuable at and beyond the known invasion front, where trapping was less intensive, and thus less background information was available. And of course, finding invasive species at and beyond the invasion front is precisely where you would most want to find the rare individuals as they start to show up.

More generally, this example points out the value of eDNA for data-poor situations worldwide. Once you know how well your assay works, it’s quite likely to be most valuable in places where we have relatively little information in-hand.